100 Years: Tennessee Bridges

Ferries

As more permanent settlers arrived in Tennessee the need for more reliable river crossings became evident. Since the construction of substantial bridges was not feasible in the late 1700s and early 1800s, settlers established ferry boat operations. As the construction of bridges spread, ferry crossings became obsolete. Today TDOT operates two ferries- the Benton-Houston Ferry runs the Tennessee River and the Cumberland City Ferry operates across the Cumberland River.

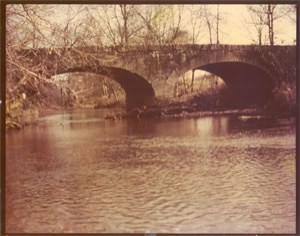

Three masonry arch bridges from the Louisville to Nashville Turnpike remain in Davidson, Robertson and Sumner Counties on little used roads. Several historians speculate the bridges were built between 1828 and 1845. The bridges which have no mortar, appear similar in construction meaning the same mason probably built them. This is the still-standing Old Stone Bridge spanning Manskers Creek at the Davidson Sumner county line.

1822 certified abutment on the Trail of Tears

Nashville’s reliance and proximity to the Cumberland River played a role in the city becoming a state leader in bridge construction. Two of the most renowned bridge engineers of the time, Lewis Wernwag and Joseph Johnson built the first wagon bridge, a toll bridge across the Cumberland River in Nashville sometime between 1819 and 1823, near where the Victory Memorial Bridge is now. This bridge carried many people across the Cumberland, including the Cherokee Indians during their forced removal to the west that became known as the Trail of Tears. As steamboat traffic on the Cumberland increased it became apparent the bridge wasn’t high enough for good clearance during high water times. It was removed in 1851 after the construction of Nashville’s second river bridge. One of the original abutments from the 1823 bridge still stands underneath the Victory Memorial Bridge today. In 2014, TDOT Maintenance crews removed harmful trees and other vegetation that threatened the abutment’s stability. Maintenance also spread grass seed and placed a fence with a lock around the abutment. In addition, TDOT Commissioner John Schroer signed a partnership agreement with the National Park Service to have the bridge abutment officially certified as part of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. Along with Commissioner Schroer, TDOT Cultural Resources Staff continues to work to ensure the abutment is properly maintained and preserved.

Bridge at Old Town spanning Brown's Creeks on the Natchez Trace, Williamson County is one of the oldest remaining man-made bridges in Tennessee. The structure consisted of massive masonry abutments with a short pole bridge suspended between them. Pole bridges were probably the most common type of bridge erected in frontier days and are still used today for simple county bridges. These bridges consist merely of poles (trees or logs) extending from one abutment to another with a deck of saplings or planks laid across the poles.

Railroad Bridges

The railroads logically led in railroad bridge design and construction. Railroad bridges carried much heavier loads than highway bridges. It was the railroad companies that probably first introduced concrete arch spans in Tennessee. Up until the early 1910s, metal trusses were the bridge of choice for county governments. Roads and bridges in the early days were built by individuals and counties. But none had regard for the bigger picture – a transportation system that connected. In the early 1900s, out of necessity, the federal government took over and passed a bill that provided $75 million to be spent on roads but only in states with organized highway departments. Tennessee created its department in 1915. Its members decided immediately the top priorities would be the Memphis to Bristol Highway and the Dixie Highway which spanned from Chattanooga to Nashville and eventually further north into Kentucky.

The first documented concrete roadway in Tennessee was a portion of Woodmont Boulevard in Davidson County. Real estate developers built the two mile stretch of 32-foot wide roadway in 1914.

Standardization of bridges

By 1927 the highway department began to standardize the types of bridges it built. By the end of the decade Tennessee laid claim to thousands of miles of paved two lane roads with hundreds of modern bridges and a standard speed limit in rural areas of 30 mph.

Tennessee became the first state in the nation to pursue the matching federal funds at a statewide level when Governor Austin Peay and the Tennessee Legislature created a "Special Bridge Program" on January 19, 1927. This program started with $11.5 million that created a bridge-building program with bonds serviced by tolls. The bridge-building program included funds for 17 bridges essential to completing the state highway system. Four more bridges were eventually added to the original program. Sixteen were brand new and one was an existing private toll bridge at Carthage purchased by the state highway department. All of the toll bridges built through this programmed were freed between 1939 and 1947.

New Deal revives bridge building

During the depression, road and bridge building significantly declined until President Roosevelt’s New Deal brought it back to life. In 1933, under the New Deal programs, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was created mainly to solve many of the problems in the Tennessee River watershed which involved Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Kentucky. Because the Tennessee River is mostly located in Tennessee it directly affected bridge construction in the state. Between 1933 and 1941 the TVA built a hydroelectric network of nine major dams and lakes. TVA relocated the metal truss bridges or just raised them to accommodate the rising waters. They had no choice but to demolish the concrete arch bridges that flooded. The Civilian Conservation Corps was also part of the New Deal as a public relief program which benefited state transportation systems. In Tennessee many bridges were built as part of this program.

Interstate System is initiated

After WWII road and bridge building picked back up again. Congress, under President Eisenhower, created the Highway Trust Fund. The law required all funds raised through user taxes on trucks, tires, gas, etc. to be spent on transportation purposes. Tennessee's Senator Albert Gore, Sr. was one of its backers.

Gore was a major sponsor of the 1956 Federal-Aid Act. It provided $25 billion for 12 years to fund the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. The 41,000 mile network of superhighways would connect every major city in the U.S. The network eventually expanded to 42,800 miles.

Bridge collapse results in changes

No one was prepared for what happened on April 1, 1989. Three spans of the north bound lanes of US 51 over the Hatchie River collapsed and sent eight people to their deaths. This tragic incident and the investigation of the bridge failure resulted in the TDOT Bridge Inspection Program becoming one of the most respected in the nation. With this failure and a 1987 collapse in New York, the FHWA strengthened its enforcement and training on stream scour (erosion) and detection of scour on all bridges in the nation in 1991. Analysis and design manuals were developed for addressing scour at bridges. Scour design for new bridges is now a standard practice for all hydraulics engineers. Since that time, Tennessee has increased its expenditure on bridges to well over $100 million compared to $1 million before the 1989 failure.

Quaking bridges

In west Tennessee earthquakes are also an issue. Traveling from the east to the west coast, I-40 is a life line through the nation. As the talk of a possible earthquake along the New Madrid Fault Line increased in the 1990s, TDOT bridge engineers began to assess the risk of failure to the Hernando DeSoto Bridge (I-40) across the Mississippi River in Memphis. Thus began a 15-year seismic retrofit project designed to protect this bridge and its approaches in the case of an earthquake of up to 7.7. The bridge is located along the same fault line that erupted in an 1811 earthquake that created Reelfoot Lake in Lake County, Tennessee. Due to the importance of I-40, assessments showed that a $4.5 billion economic impact to the U.S. would occur if the bridge were lost. The project is a collaborative effort between TDOT and our Arkansas state partners with well over $200 million dollars spent by completion in 2015.

Tennessee bridges today

There are 19,721 bridges on public roads in the state of Tennessee. These bridges fall into two categories for the purpose of distributing state and federal funds. On-System Bridges are those maintained, owned and operated by the state. They are found on the Interstate System, the National Highway System and the State Route System and include 8,272 bridges. Off-System Bridges are those found on roads owned, maintained and operated by local governments that include counties, cities and towns in Tennessee. Those number 11,449. TDOT has 17 inspection teams that inspect all on-system and off-system bridges. On average, three bridges a day are inspected by each team.

In 2009, TDOT began a Better Bridges Program, the largest bridge program ever to address 200 structurally deficient bridges. In four years, TDOT replaced or repaired 200 state owned bridges reducing the number of structurally deficient bridges on local and state systems to 5.9 percent. This brought Tennessee far below the national average of 11 percent. TDOT's bridge program is one of the best in the nation. In 2013 CNBC ranked Tennessee 2nd in "America's Top States for Transportation and Infrastructure."

In TDOT's 100 year history there have only been six directors over the structures division.