Tennessee Clean

Tennessee Clean (TN Clean) is a program to revitalize some of Tennessee’s most downtrodden and polluted sites. The sites on the TN Clean list were former industrial facilities such as dry cleaners, metals smelters, automobile recyclers, assembly plants, and more that were polluted by industry. The State is obligated to fund investigation and cleanup of existing pollution on these sites which could be impacting human health, the environment, and their communities’ economic growth potential. Many of these sites have languished for years and remain unsuitable for redevelopment.

The State of Tennessee has inherited responsibility for these sites, though, until recently, many had no remaining funding to clean them up. In 2022, Governor Bill Lee and the Legislature began to set aside funding for the State to investigate and remediate these sites. Investment through TN Clean will improve Tennessee’s environment, support economic growth, and promote community vitality and sustainability by unlocking acres for redevelopment and opportunity that had been previously considered unusable.

Most TN Clean sites are managed by TDEC’s Division of Remediation, though several sites belong to the Division of Solid Waste Management, and one site falls under the jurisdiction of the Division of Radiological Heath.

Explore the tabs below to see each division's TN Clean sites or click the button below to explore the ArcGIS StoryMap describing the TN Clean program.

Current TN Clean Sites

Division of Remediation

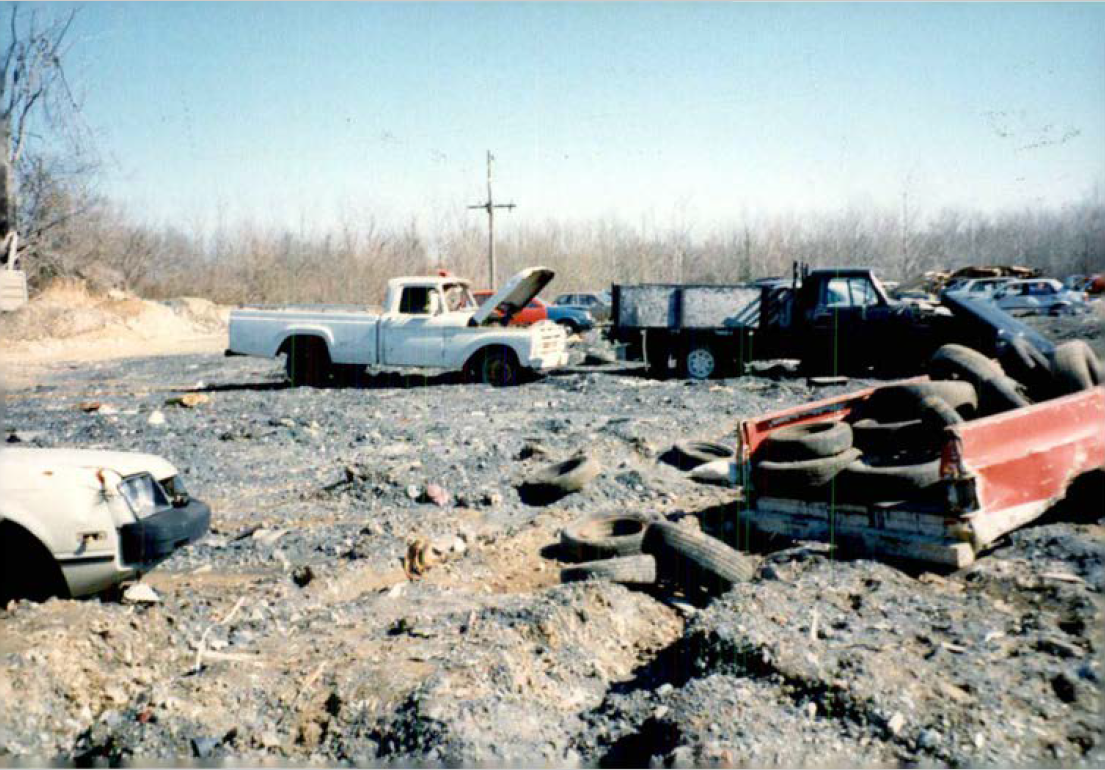

The Atomic City Auto Parts site was a former automobile junkyard and scrap metal recycling facility located in Oak Ridge. DoR used a state remediation contractor to complete an interim removal action in 2003-2004 as part of a negotiated agreement with US Department of Energy (DOE), who was the responsible party. Contaminated soil and debris was excavated and removed for offsite. TDEC conducted a cleanup of this site that was completed in 2005. Based upon a review of TDEC's confirmatory sampling conducted after cleanup was completed, the DOE believes that TDEC 's cleanup objectives for the site have been met and TDEC concurred in a letter to DOE in October 2021. The only remaining actions for this site are development of a Risk Assessment (assigned to DOE), development of a Record of Decision, recording of a Notice of Land Use Restriction (NLUR) and the delisting process. No further remediation is required.

This property was an audio speaker assembly plant for the company Electro-Voice, previously owned by Mark IV Industries. The assembly plant was in operation from the mid 1960s until 2001. This former industrial site has been monitored since 2001 for chlorinated solvent chemicals that leaked from an underground storage tank. Groundwater, soil, and air on this property have been sampled for these cleaning chemicals to ensure that the concentrations are low enough to be safe for workers on the site now and in the future. Groundwater contamination is currently present in three monitoring wells at the property.

This site has shown evidence of chlorinated solvent contamination in groundwater on the property and on neighboring properties. The 20-acre parcel has been used by a variety of manufacturers, but the contamination has been mostly attributed to the steel tubing, plating, and fabrications manufacturer, Wall Tube & Metal Products, which operated here from 1956 until 1983. The property owner removed waste materials left behind by Wall Tube & Metals in 1985 before a TDEC report from 1986 indicated that metal plating sludge, paint sludge, and chlorinated solvents were contaminants of concern at the site. Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, TDEC and the EPA assessed the extent of contamination and devised remedial plans to address it. In 1997, TDoR removed contaminated soil from the facility. The most recent investigation of the site occurred in 2005, which found that chlorinated solvent contamination was still present at the site and appeared to be migrating off-site. Today, TDoR is investigating groundwater and soil gas to evaluate the current state of contamination.

Between 1963 and 1974, Velsicol Chemical Plant disposed of herbicide and pesticide residues in drums on a neighboring property, now known as “Residue Hill”. They also used settling ponds on the hill to remove some chemicals from wastewater. Open pits used for waste disposal were covered by a clay cap in 1973, when site investigations showed contamination in groundwater and soil at the site. The EPA removed some of the waste in the 1970s before an 18-acre cap was installed over the landfill to prevent contamination in surface waters and air pathways. Groundwater has been monitored since 1980. A thorough assessment of groundwater and soil has been launched in 2023 to identify current concentrations of herbicides and pesticides and their chemical byproducts. Benzoic acid was identified as the largest contributor of contamination, along with lower concentrations of VOCs and pesticides.

Morningside Chemical manufactured dyestuffs for the carpet industry from 1978 until 1983, when the property changed hands. Morningside bought the 1.5-acre property in 1976, after a fire at the site had put its previous owners (Vol State Chemical Company) out of business. The fire in 1976 damaged several tons of industrial chemicals owned by Vol State Chemical, the previous owners of the property, which were then buried illegally in trenches on the property. In 1985, The TN Department of Health and Environment (predecessor of TDEC) received an anonymous complaint alleging that hazardous chemicals were illegally disposed of and stored in the facility’s basement. Upon inspection, it was discovered that 170 drums had been placed in the basement after the 1976 fire leveled the warehouse, and up to 40,000 gallons of contaminated water filled the basement. In 1993, 625 drums containing acids, bases, and dyes were found in a different warehouse on the site, at which point the US EPA conducted an emergency removal of the waste. The most recent sampling event in 2003 indicated that groundwater is impacted by metals, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and semi-volatile organic compounds. TDEC is investigating the site today to evaluate current levels of contamination to inform potential remedial action.

This 39-acre site contains a former landfill that contains municipal and industrial waste. The landfill operated from 1971 until 1979, when it was improperly capped and closed. Portions of the landfill were sold as residential properties. In 1988, well water in private drinking wells was sampled and organic contaminants were detected. The US EPA found that local groundwater, soil, sediment, and surface water were all contaminated with organic and inorganic compounds from the landfill. The landfill sits on a limestone ridge, providing karst transport of contaminants into groundwater. In 2002, the landfill was properly capped and gas vents were installed. Today, TN Clean is taking financial responsibility for the site to continue annual inspections and other routine maintenance. No remediation is required.

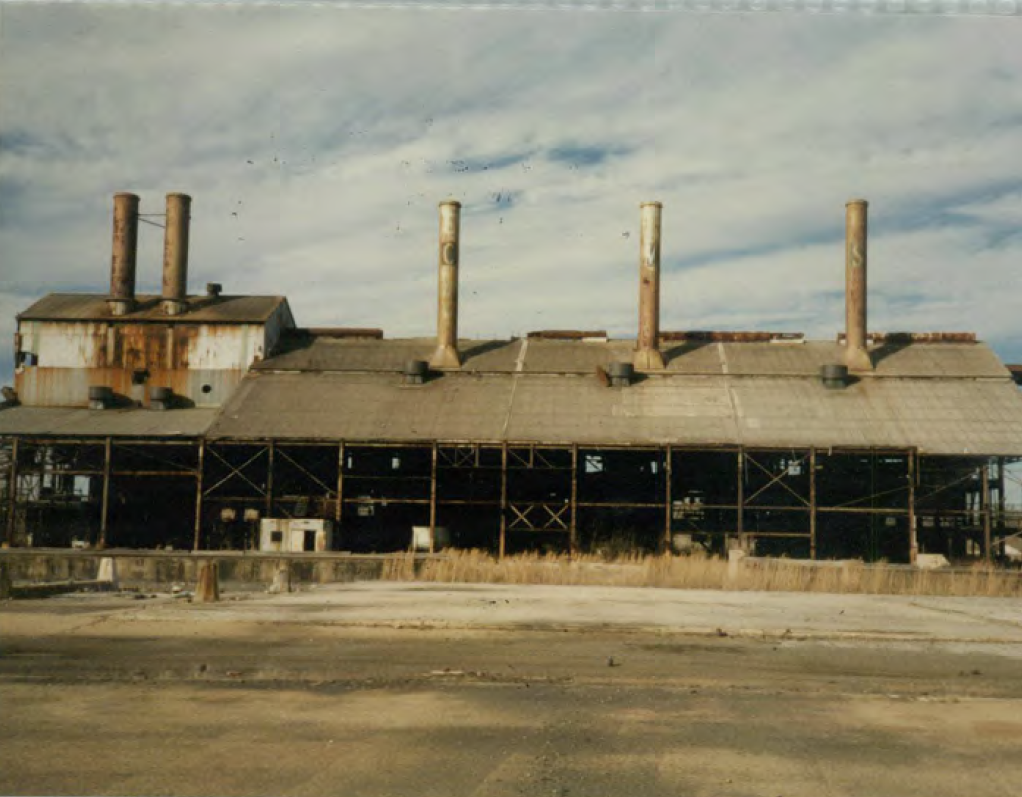

This site’s industrial history dates back to 1897, when Roane Iron Company produced iron products there. Various industrial operations have taken place on the site, including coal mining, coke fuel production, pig iron production, and automobile shredding. Automobile shredding – the shredding of seats, carpets, and other soft car parts – took place on the site from 1974 to 1987. These shredding operations left piles of automobile shredder residue containing plastics, rubber, wood, fabric, glass, metal fragments, and contaminants such as metals, PAHs, and PCBs on the site. From 2001-2004, TDEC devised and implemented a plan to consolidate and cap the residue into three piles and to install a leachate treatment system. The site has been inspected regularly inspected since 2004 and operation, monitoring, and maintenance of the landfill has continued since then. This remedial action was paid for by the responsible party until they filed for bankruptcy in 2016, and the State picked up the liability for the site. TDEC is currently reassessing the site with TN Clean funds and continuing operation and maintenance activities.

The Joyner Scrap Yard operated on this property in Kingston from purchase in 1967 until 1988. Mr. Joyner purchased scrap and surplus items from the US Department of Energy (DoE) and resold them to the public, leaving behind metals, PCBs, and radiological contamination on the site property. From 1997-1999, TDEC surveyed and removed all radiologically contaminated items from the site, and removed chemically hazardous materials in 2000. It is believed that all radioactive items and containers of hazardous chemicals have been removed from the property, but an investigation in 2001 concluded that soils and groundwater were still significantly contaminated and warrant further investigation and possible remedial action to fully restore the site. Today, TDEC is reinvestigating monitoring wells on the site to assess groundwater contamination and conducting soil sampling to assess remaining contamination in the soil so that remedial strategies can be deployed to restore this site to full productive use.

In 1994, TDEC responded to a report that abandoned drums had been discovered on a property owned by Mr. Roscoe Fields. Upon inspection, the drums appeared to have been purchased by the Department of Energy (DOE) in the 1970s from their Oak Ridge facility. A radiological survey indicated that several drums had radiation readings above background levels, and an emergency removal was conducted. During this removal, 239 drums, 390,780 pounds of contaminated soil beneath the drums, and miscellaneous scrap material from the DOE were characterized and disposed of. Contaminants detected in the waste included metals, VOCs, PCBs, cyanide, and radioactive isotopes of uranium. Today, TDEC is reexamining the site to assess the current state of contamination of groundwater.

From 1971 to 2002, the Dixie Barrel & Drum Co, Inc., operated a plastic and steel drum recycling and reconditioning facility. Permitted to accept drums containing on more than 1 inch of product remaining, drum material would be emptied into on-site storage tanks before the drums would be cleaned and restored through chemical processes. In 1980, testing of waste material indicated the presence of pesticides, heavy metals in the sludge, and the facility was subjected to hazardous waste regulations by TDEC. In 2002, the facility filed for bankruptcy and was abandoned. The DoR inspected the facility in 2003 and found large quantities of potentially hazardous substances. Drums were stored next to incompatible chemicals, evaluating the risk of fire and explosion, and the spillage collection system had been leaking oil into the concrete block walls of the building. The DoR referred the site to the EPA’s Emergency Response and Removal Branch (ERRB). The ERRB removed approximately 1500 drums, a waste pile of scrap metal and crushed drums, above ground storage tanks, and 592 tons of contaminated soil from the site in 2005. The main building was demolished in 2010. Today, TDEC is re-investigating the property with TN Clean funds to restore it to full productive use.

Division of Solid Waste Management

Learn more about the Division of Solid Waste Management.

Learn more about the Division of Solid Waste Management.

Learn more about the Division of Solid Waste Management.

Division of Radiological Health

Division of Remediation

The Old Murray Ohio plant in Lawrenceburg, TN was a producer of bicycle parts and lawn mowers from its construction in 1956 until closure in 2005. An environmental assessment in 2006 found contamination in groundwater. A variety of contaminant types were identified, including metals, VOCs, chlorinated solvents, and petroleum products. The facility stored its hazardous waste in drums on site; some contamination may have been contributed through leakage of these drums or through their production and use during manufacturing. Although limited assessment has been performed, the site will require a complete site characterization to determine the nature and extent of contamination.

In the 1960s and 1970s, this landfill accepted household and industrial wastes, the latter containing PCB, VOCs, and chlorinated solvent contaminants. Water quality issues arose in the 1970s, and the landfill was covered with a 2-foot clay cap in 1982. Concrete drainage channels and a clay-lined settling pond were installed to divert stormwater and collect potential leachate. In 2010, TDEC sampled the adjacent Beech Creek, drinking water wells, sediment, and surface water wells; PCBs were identified in Beech Creek sediment and floodplain soil. Soil and sediment containing elevated levels of PCBs was removed in 2015-2016. TDEC is reinvestigating the site to determine current groundwater conditions and characterize seeps that may be present at the base of the dump.

Division of Solid Waste Management

Learn more about the Division of Solid Waste Management.

Learn more about the Division of Solid Waste Management.

Division of Remediation

A drycleaner operated at the site from 1945-1977. In 1992, the site’s soil and groundwater were found to be contaminated with several chlorinated chemical that had leaked from an underground storage tank. The site has been monitored and tested since 1997 to define the contaminated area. Contamination was found to have spread beyond the site boundaries into neighboring properties. Several Injections of maple syrup, soybean oil, and simple green emulsion into injection wells in the ground began in 2002 to encourage biological activity at the site. This continued for about a year. A source area approximately 22 feet by 22 feet and about 12 feet deep was discovered where the building used to sit. Later in 2004, about 215 cubic feet of contaminated soil was removed. Sodium lactate was added to the bottom of the pit to sustain biological activity; the pit was then refilled with clean gravel and soil. Since 2004, about every 6 months sodium lactate is added to the onsite injection wells. The onsite wells are sampled to evaluate the effectiveness of the injections. Although concentrations in groundwater have decreased due to the various injection activities, significant contamination remains.

From 1978 to 1992, Ross Metals produced lead alloys for manufacturing car batteries, lead-shot pellets, and sheet lead used for radiation shields. These alloys were produced by smelting spent lead-acid batteries, lead plates, scrap metal, and lead waste from other manufacturing sources. Production generated wastes such as lead dust, plastic chips, lead-contaminated stormwater, and especially large quantities of blast slag. 10,000 cubic yards of this lead-contaminated slag was buried onsite in an unlined landfill, and another 6,000 cubic yards was stockpiled around the property. In 2001 and 2002, contaminated buildings on the property were demolished, contaminated soil was excavated and removed, metal debris was recycled, and site wetlands were revegetated as part of a remedial action. Groundwater monitoring is ongoing, though there is no additional remedial action necessary.

The Creotox Chemical Company was a pesticide blending facility from approximately 1946 to 1991. The TDEC Division of Solid Waste Management conducted an inspection of the property in 1985 which indicated there was some spillage of pesticide chemicals around the facility. Drums containing hazardous substances were found in the facility in 1995, and subsequently removed after soil testing showed contamination in a nearby drainage ditch. The EPA conducted an emergency removal of 45 cubic yards of hazardous debris, 3 drums of hazardous liquids and solids, 3 drums of non-hazardous solids, and 2,117 tons of contaminated soils, which was completed in 1997. Soil and groundwater were tested again in 2003 and once more in 2007. The presence of contaminants in groundwater have been decreasing, though there is some evidence of contaminants move downgradient with groundwater flow. TDEC has conducted significant remedial work on this site in the past, and it is almost ready to be made available for reuse.

The Chromium Mining and Smelting Corporation (Chromasco) smelted metals in Memphis from the early 1950s until 1984. This 92-acre site has been monitored since the 1980s for metals, notably chromium and arsenic, in groundwater, soil, sediment, and surface waters. Contaminated sediment, soil, and drums containing waste were excavated and removed from the site in 2000, but recent sampling indicated that there is still some remaining contamination. The site is currently being evaluated to assess the protectiveness of prior site remedial activities and institutional controls.

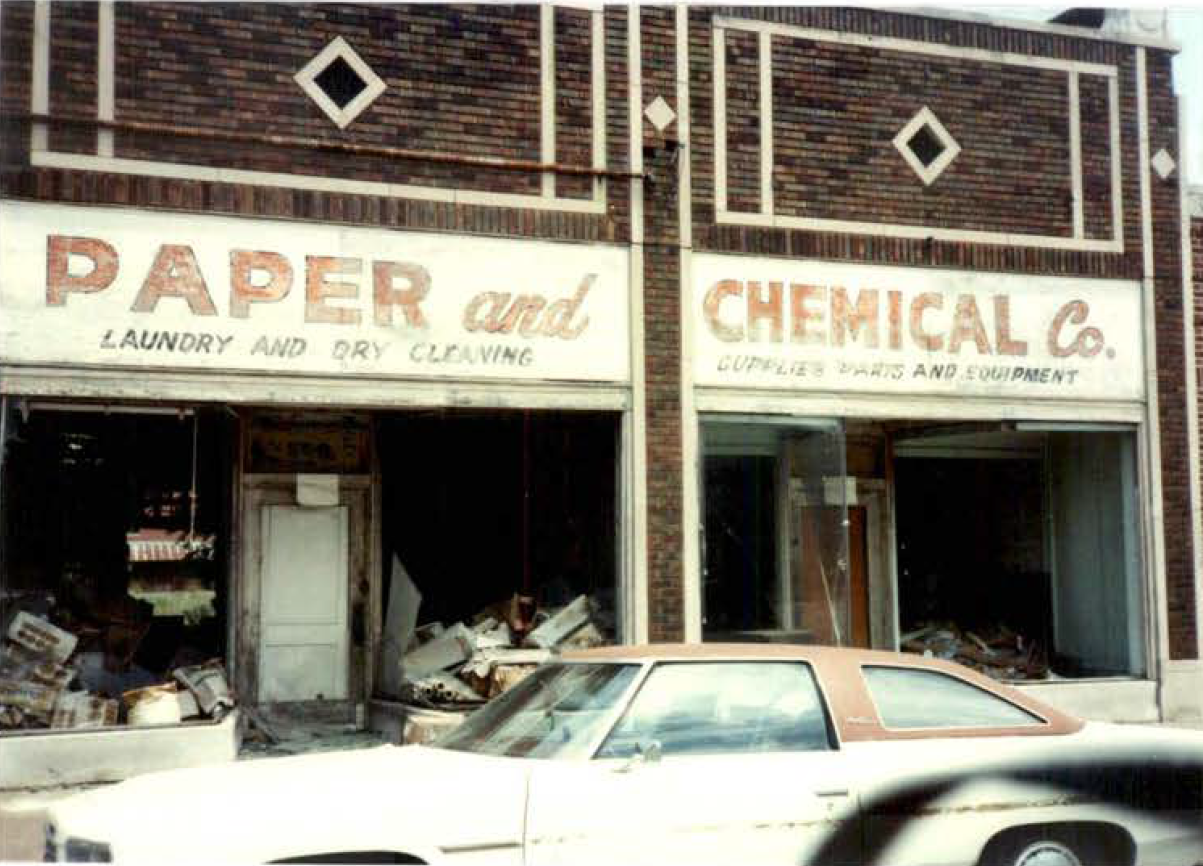

The National Paper and Chemical company operated in Memphis from 1946 until the mid-1970s. After the company closed, the operator, John Little, stored more than twenty-five 55-gallon drums and numerous smaller containers of dry-cleaning chemicals and a large quantity of paper products in a vacant building on the property. Vandalism and lack of maintenance led to disarray and chemical spills in the building in the mid-1980s. In 1986, TDEC and the Memphis Fire Department inspected the facility after receiving a complaint about the stored drums and conducted an emergency removal in 1987, and the building was subsequently demolished. Investigations of the soil and groundwater in the 1990s indicated elevated levels of chlorinated dry cleaning chemicals and daughter products. Neighboring properties also showed elevated levels of these chemicals in the soil and soil vapor. TDEC is currently working to identify and remove source material in the soil and potentially groundwater to remediate the site.

This 15-acre area was used as a gravel excavation pit until it was abandoned. Thereafter it was used to store old highway equipment. In the mid-1970s, several 55-gallon drums containing paint wastes were buried illegally at the site and began leaking. The site was investigated by the former Tennessee Department of Health and Environment in 1982. The Boneyard was promulgated as a State Superfund site in 1987. After this designation, the TDoR tested the soil and groundwater at the Boneyard throughout the 1990s. Approximately 4800 cubic yards of contaminated soil, drums, and debris were removed in 1994 and replaced with clean soil. The site is currently being monitored to assess the migration of these chemicals in the groundwater to neighboring properties.

Fiberfine is the site of an inactive rock wool manufacturing plant. Rock wool is made by melting rock and spinning it into fibers, which also produces slag wool as waste. The slag, which contains lead and other heavy metals, was disposed of in a pile on site along with contaminated soil and sediment. When the factory was demolished in 1994, some of the slag was pushed into a nearby wetland area, causing contamination. The EPA excavated 5,000 cubic yards of waste slag and 16,000 yards of contaminated soil and disposed of them in a properly capped pile. Further sampling of site soils and groundwater is required to verify proper/current characterization of site impacts and if contaminant migration has occurred.

Chapman Chemical began producing wood preservatives and agricultural chemicals in 1941. Through the production of an herbicide, a sodium chloride byproduct containing arsenic and pesticides was stored in a 0.5-acre salt pond on the property. The property was sold to Valley Products, Inc., in 1994 and was subsequently investigated for contamination. The pond was filled in with clean dirt and covered with gravel and asphalt in 2000. The site has not been sampled since 2000, so TDEC is reinvestigating the site today to determine the efficacy of the asphalt cap to stop transport of contaminants.

Division of Solid Waste Management

Learn more about the Division of Solid Waste Management.